Systems Thinking Meets Simplicity-First: A Decision Framework for Software Architects

- Chris Woodruff

- January 23, 2026

- Simplicity-First

- architecture, design, simplicity-first, systems thinking

- 0 Comments

Modern technology operates in a paradox. Our tools have never been more powerful, yet our systems have never felt more fragile. Every framework, pipeline, and process claims to simplify development, but most end up multiplying dependencies and eroding clarity. In that chaos, two guiding philosophies emerge: Systems Thinking and Simplicity-First.

At first glance, they seem to occupy opposite ends of the spectrum. Systems Thinking invites us to embrace complexity, to see the world as an intricate web of interrelated parts. Simplicity-First urges us to strip away complexity, to build only what’s essential and resist the cult of cleverness. But these philosophies are not opposites. They are complements. Together, they form a balanced framework for understanding complexity without surrendering to it, enabling the building of coherent, sustainable, and humane systems.

Seeing the Whole: A Shared Rejection of Reductionism

Both Systems Thinking and Simplicity-First reject reductionism, the tendency to break problems into isolated parts and optimize them independently.

Systems Thinking emerged from fields like ecology, cybernetics, and organizational theory as a response to linear cause-and-effect thinking. It views every problem as part of a larger system, where changes create ripples through feedback loops and dependencies. A system cannot be understood solely by examining its components; it must be understood in terms of how those components interact.

Simplicity-First, while rooted in software development, embraces a similar holistic vision. It argues that simplicity is not achieved by simplifying individual functions or microservices, but by simplifying the relationships between them. True simplicity lies in cohesion, in how well the parts of a system fit together and communicate with one another.

These two philosophies converge in their insistence that context matters. An elegant algorithm or efficient service means nothing if it introduces friction or opacity into the broader ecosystem. The overall health of the system is more important than the cleverness of its individual parts.

Complexity: To Manage or To Remove?

Here, the two philosophies reveal their distinct but complementary strengths.

Systems Thinking recognizes complexity as a fundamental aspect of living systems. Rather than viewing it as a challenge to be eradicated, Systems Thinking seeks to manage complexity by deepening understanding of information flows, energy, and feedback that influence behavior over time. From this perspective, complexity is not a drawback but a potential source of adaptability and resilience.

Simplicity-First asks the question most architects avoid: does this complexity actually need to exist? It draws a hard line between essential and accidental complexity, as outlined in Fred Brooks’ influential essay “No Silver Bullet.” Essential complexity is inherent to the domain we’re modeling. Accidental complexity arises from design missteps, over-engineering, and needless abstractions.

The practice of Simplicity-First involves ruthlessly identifying which elements of a system are intrinsic and which are imposed. Systems Thinking provides the analytical tools to trace interconnections; Simplicity-First supplies the discipline to cut what shouldn’t be there.

Case Study: The Service Extraction Decision

Theory becomes meaningful only when it changes decisions. Consider a scenario I encounter regularly: a team wants to extract a “Notification Service” from their modular monolith. The feature handles email, SMS, and push notifications. It has clear boundaries. It seems like an obvious candidate for extraction.

Let’s apply both frameworks to this decision.

The Systems Thinking Lens

First, we map the dependencies. The notification module touches user preferences, order events, marketing campaigns, and authentication flows. It reads from a shared database and publishes to a message queue that three other modules consume.

Systems Thinking reveals the feedback loops: when notifications fail, customer support tickets increase, triggering escalation emails that depend on… the notification system. We see that this “isolated” module is actually a hub in our system’s information flow.

The Simplicity-First Lens

Now we apply the 2 AM Test: if this service fails at 2 AM, can an on-call engineer understand and fix it without the original authors? A separate notification service means maintaining a deployment pipeline, a separate monitoring stack, network partitioning scenarios, and distributed transaction semantics. The engineer must now reason about two systems instead of one.

The Half-Rule asks: can we solve this problem with half the components? The monolith already handles notifications. What problem are we actually solving by extracting it?

The Decision

In most cases, the answer is: keep it in the monolith. The “cleanliness” of a separate service is accidental complexity masquerading as good architecture. Systems Thinking showed us the hidden dependencies; Simplicity-First gave us permission to reject the extraction.

The exception proves the rule: if the notification system genuinely needs independent scaling (millions of messages per hour), or if a separate team will own it with clear API contracts, extraction may be justified. But that decision should be driven by measured pressure, not architectural fashion.

Conceptual Comparison

| Theme | Systems Thinking | Simplicity-First | Intersection |

| View of the World | Sees reality as a web of interconnected systems where every part influences the whole. | Views software, teams, and organizations as systems that must stay understandable and cohesive. | Both reject reductionism and silos, emphasizing context and interdependence. |

| Relationship with Complexity | Accepts complexity as intrinsic to living systems and seeks to manage it. | Distinguishes essential from accidental complexity, aiming to eliminate the latter. | Together they form a balance: understand what must stay complex, simplify what need not be. |

| Goal Orientation | Strives for systemic balance, resilience, and sustainability. | Strives for clarity, maintainability, and sustainability through reduction of waste. | Both optimize for long-term stability over short-term speed. |

| Change & Adaptation | Encourages continuous feedback and learning to adapt the system. | Embraces iterative simplification: refactoring, pruning, and redesigning based on feedback. | Both view improvement as an ongoing loop rather than a one-time event. |

| Human Role | Recognizes human limits and cognitive biases within systems. | Designs within human cognitive capacity: favoring understandable over clever. | Both center the human as the system’s most fragile but essential component. |

| Ethical Foundation | Promotes responsibility for systemic consequences and unintended effects. | Advocates for ethical restraint: building only what adds value, avoiding wasteful over-engineering. | Both align with sustainable and humane technology practices. |

Practical Application

| Dimension | Systems Thinking in Practice | Simplicity-First in Practice | Synergistic Outcome |

| Architecture | Maps dependencies, flows, and feedback loops between services, teams, and stakeholders. | Consolidates unnecessary layers, favors modular monoliths, and limits external coupling. | You understand why systems become tangled, and know how to untangle them. |

| Decision-Making | Evaluates impact of decisions across the entire system. | Uses the Half-Rule and 2 AM Test to choose minimal viable options. | Leads to balanced, context-aware choices rather than fashionable ones. |

| Team Communication | Builds shared mental models of how the system works. | Simplifies vocabulary, diagrams, and documentation to make knowledge accessible. | Shared understanding improves coordination and reduces design entropy. |

| Development Process | Uses causal-loop diagrams and retrospectives to surface feedback. | Implements feedback through code review, architectural refactoring, and iteration. | Continuous learning leads to continuous simplification. |

| Measurement | Monitors system health using flow efficiency, defect rates, and stability. | Measures simplicity through cognitive load, maintainability, and energy use. | Both provide actionable metrics for sustainable improvement. |

| Leadership & Culture | Encourages cross-functional collaboration and long-term thinking. | Rewards clarity, humility, and stewardship over cleverness. | Creates organizations where technology and culture evolve coherently. |

Feedback and Learning: The System That Simplifies Itself

Both philosophies treat improvement as a continuous process, not a destination.

In Systems Thinking, feedback loops are the mechanism through which systems learn and adapt. Reinforcing loops amplify changes; balancing loops maintain stability. By understanding these dynamics, leaders can create systems capable of self-correction.

Simplicity-First applies this principle to design. Teams refine code, streamline features, and adjust architecture based on real-world feedback. A simple system is not one that was designed perfectly from the start. It’s one that grows and evolves responsibly through continuous pruning.

This creates a dynamic equilibrium: continuous adjustment without chaos. Both disciplines provide tools to recognize when systems are drifting toward unnecessary complexity and mechanisms to guide them back toward clarity.

Finding Leverage Points

Donella Meadows, in her seminal work on systems dynamics, identified “leverage points”, places in a system where small changes produce large effects. This concept beautifully bridges Systems Thinking and Simplicity-First.

Consider a system plagued by slow deployments. A Systems Thinking analysis might map the entire CI/CD pipeline, revealing that test suites take 45 minutes because they spin up full database instances. A Simplicity-First lens identifies the leverage point: replace integration tests with contract tests where possible, use in-memory databases for unit tests. The change is small, the impact cascades through developer productivity, deployment frequency, and incident response time.

Leverage points are where understanding meets action. Systems Thinking reveals them; Simplicity-First gives us the courage to act on them.

Sustainability: The Long View

Both frameworks advocate against short-term optimization that creates long-term fragility.

Systems Thinking emphasizes that every intervention brings consequences, including unintended outcomes that may emerge years later. Sustainable systems account for these downstream effects. In organizational contexts, this means designing structures and incentives that prioritize resilience over quarterly metrics.

Simplicity-First frames complexity as debt, not just technical debt, but cognitive and ecological debt. Complex systems require more energy to operate, demand higher expertise for maintenance, and trap organizations in inflexible patterns. By embracing simplicity, we reduce waste in computation, time, and human attention.

The Human Dimension: Designing for Understanding

Both philosophies center on a fundamental truth: the key constraint in software systems is human comprehension.

Systems Thinking acknowledges that no individual can fully grasp the intricacies of a complex system. It promotes teamwork, shared mental models, and open communication to surface blind spots.

Simplicity-First takes this further: if a system cannot be understood by the team as a whole, it is too complex, regardless of how elegant its individual components may be. Systems should be designed so that understanding is distributed rather than concentrated in heroic individuals.

The Ethical Imperative of Clarity

A connection exists between these philosophies and ethical responsibility that often goes unspoken.

Systems Thinking reminds us that every decision carries unforeseen consequences. Simplicity-First adds that complexity amplifies those consequences by making them harder to trace. In an era of intricate algorithms and expansive cloud architectures, clarity is not merely beneficial. It is a responsibility.

When systems fail in ways their creators cannot explain, we have failed our users, our organizations, and our profession.

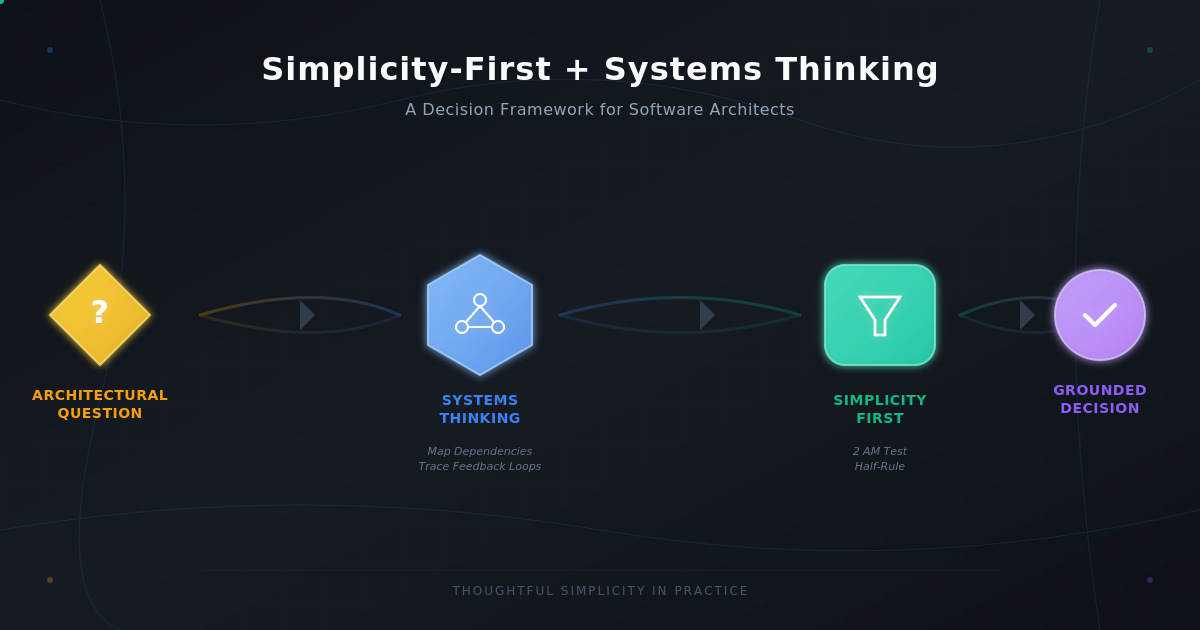

Conclusion: From Philosophy to Monday Morning

The marriage of Systems Thinking and Simplicity-First is not merely academic. It is a practical framework for making better architectural decisions.

Systems Thinking grants awareness, the ability to see complexity in its entirety, to trace feedback loops, to anticipate unintended consequences. Simplicity-First provides restraint, the discipline to act responsibly within that complexity, to eliminate what does not serve the whole.

Together, they create a philosophy of thoughtful simplicity.

What does this mean in practice? When you face your next architectural decision, whether to extract a service, adopt a new framework, or add another layer of abstraction, ask two questions. First: What are the second-order effects of this change? Map the dependencies, trace the feedback loops, and identify what this change will touch. Second: Does this complexity need to exist? Apply the 2 AM Test. Apply the Half-Rule. Be honest about whether you’re solving a real problem or performing architecture theater. The goal is not to do less. It is to do what truly matters, and to understand why it matters. Systems Thinking illuminates what matters most. Simplicity-First gives us the clarity to build it.