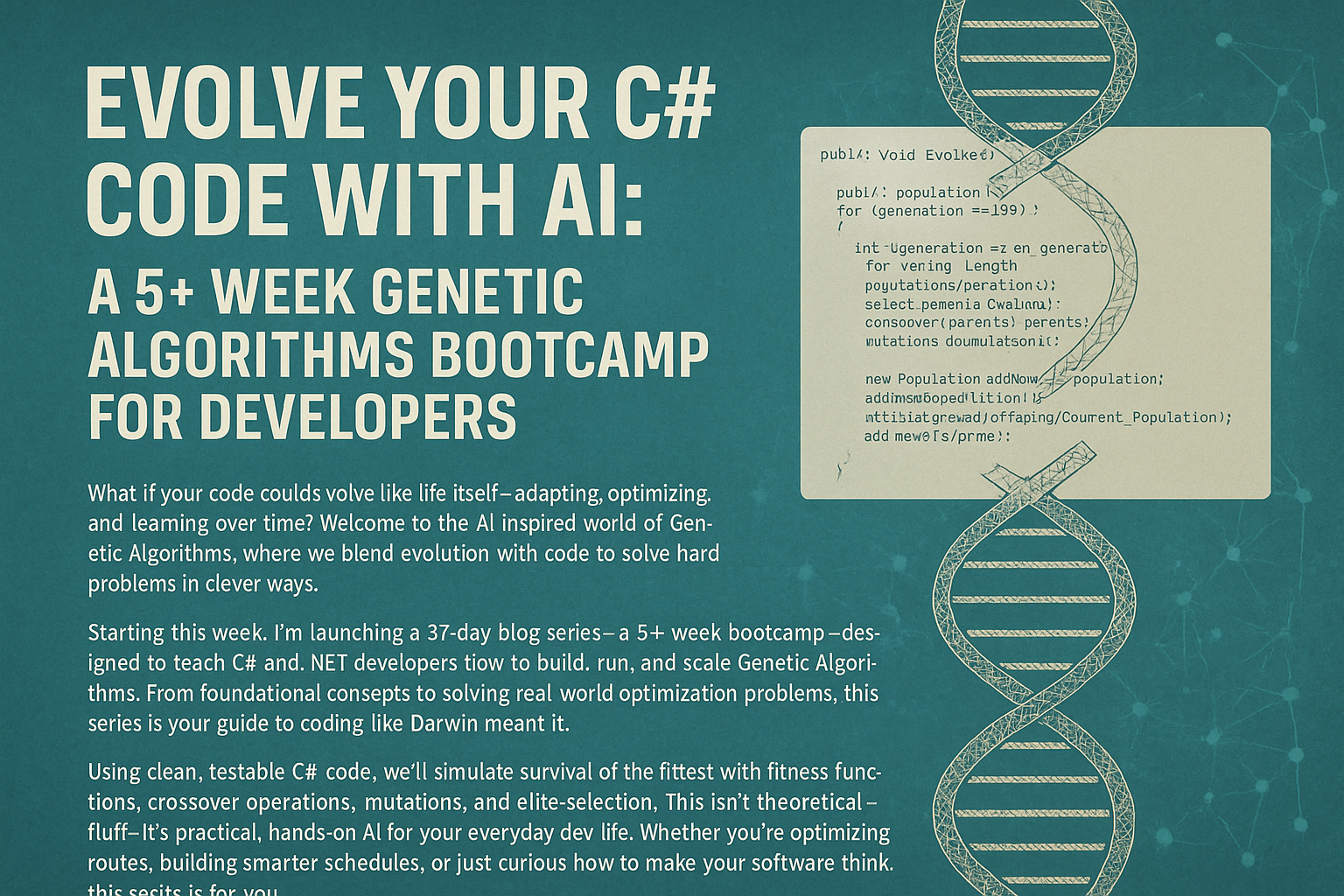

Enterprise Patterns for ASP.NET Core Minimal API: Unit of Work Pattern

- Chris Woodruff

- December 30, 2025

- Patterns

- .NET, C#, dotnet, patterns, programming

- 0 Comments

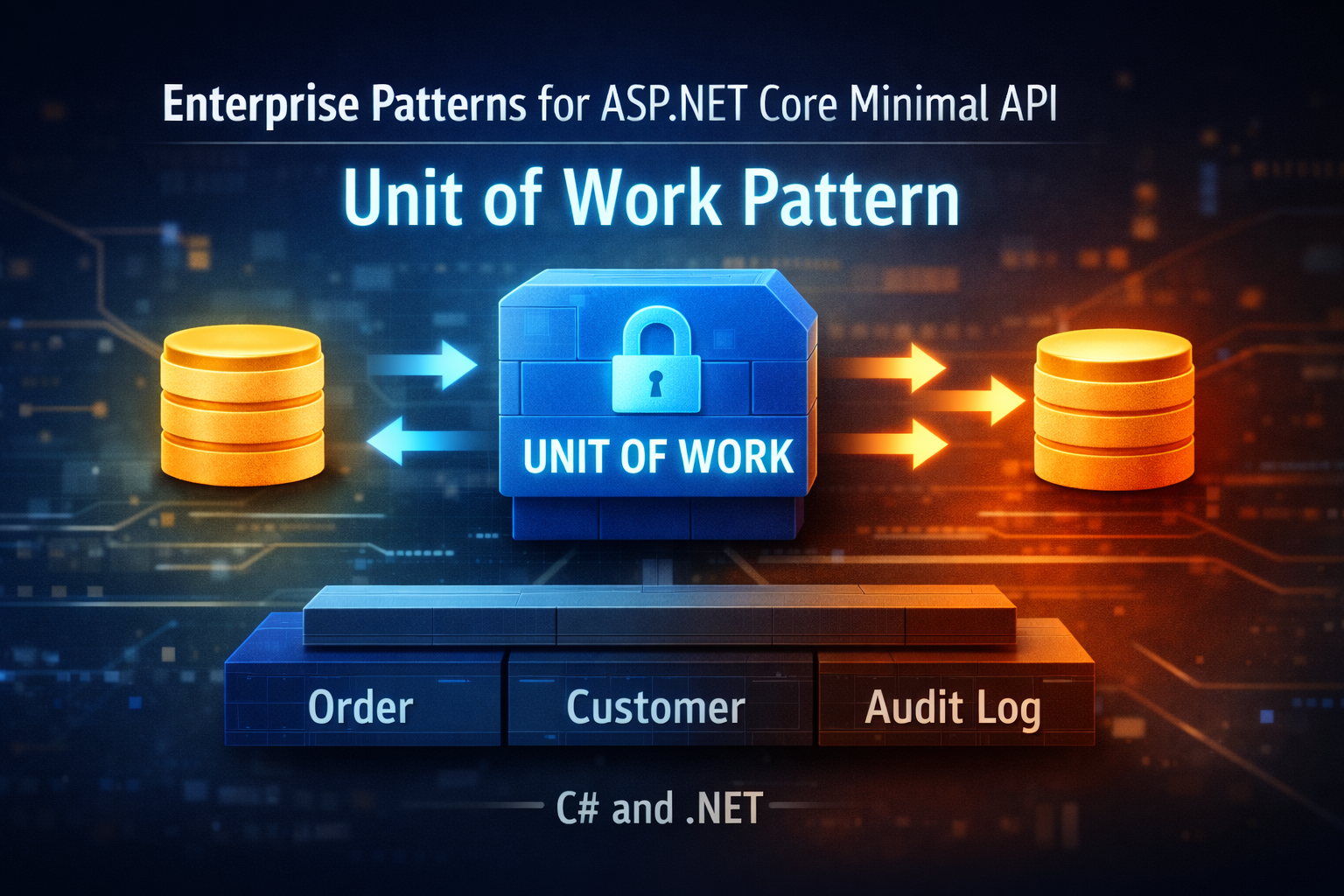

If a single business operation calls SaveChangesAsync three times, you do not have a transaction. You have a sequence of partial commits that you hope never fails in the middle.

Think about a typical “Place Order” flow:

- Create an order

- Reserve inventory

- Update customer credit

- Write an audit log

In many codebases, each step touches persistence on its own schedule. A service somewhere calls SaveChangesAsync. Another service does the same. A helper saves “just to be safe.”

Then something throws after step two and before step four. Now you have an order without inventory, or inventory without an order, or an audit log that tells a story that never really happened.

The Unit of Work pattern exists precisely to stop that.

A Unit of Work:

- Tracks changes to domain objects across a business operation

- Commits them as a single, consistent change

- Gives you a clear boundary: this use case either succeeds or fails as one

In .NET, EF Core’s DbContext already behaves like a Unit of Work. The problem is that many teams leave that fact implicit and let DbContext leak everywhere. Naming Unit of Work explicitly lets you take control of persistence again.

This post walks through:

- A practical Unit of Work abstraction for ASP.NET Core and EF Core

- Before and after Minimal API snippets

- How it plays with repositories and application services

- When the pattern earns its complexity and when it does not

What the Unit of Work Pattern Really Is

In Fowler’s terms, a Unit of Work:

- Keeps track of everything you do during a business transaction

- Knows how to persist those changes together

- Ensures that either all changes are committed or none are

In modern .NET:

DbContexttracks changes to entitiesSaveChangesorSaveChangesAsyncpersists them, often in a transaction

So why bother with a Unit of Work abstraction?

Because without it, you get:

- Multiple contexts per request

SaveChangesAsynccalls scattered across repositories and services- No obvious place that defines “this is the commit point for this use case”

A named Unit of Work lets you express that boundary in code.

A Simple Unit of Work Abstraction

Start with a minimal interface that conveys intent.

public interface IUnitOfWork

{

Task BeginAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

Task CommitAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

Task RollbackAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

}

Here is a straightforward EF Core implementation:

public class EfCoreUnitOfWork(AppDbContext dbContext) : IUnitOfWork

{

private readonly AppDbContext _dbContext = dbContext;

public Task BeginAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

// With one DbContext per request, EF Core will open a transaction when needed.

// If you introduce explicit transactions, begin them here.

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

public async Task CommitAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

await _dbContext.SaveChangesAsync(cancellationToken);

}

public Task RollbackAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

// If you add explicit transactions, roll back here.

// With implicit transactions, you may rely on exceptions to abort work.

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

}

This looks almost trivial. That is the point. It takes the implicit behavior of DbContext and turns it into an explicit concept that higher layers depend on.

If later you decide to introduce explicit database transactions, outbox patterns, or cross-database coordination, you have a place to evolve that logic without rewriting business services.

The Domain: Order And Customer

To show a realistic Unit of Work, use a simple domain.

public enum OrderStatus

{

Draft,

Active,

Paid,

Cancelled

}

public class Order

{

private readonly List<OrderLine> _lines = new();

private Order(Guid id, Guid customerId)

{

Id = id;

CustomerId = customerId;

Status = OrderStatus.Draft;

}

public Guid Id { get; }

public Guid CustomerId { get; }

public OrderStatus Status { get; private set; }

public IReadOnlyCollection<OrderLine> Lines => _lines.AsReadOnly();

public decimal TotalAmount => _lines.Sum(l => l.Total);

public static Order Create(Guid customerId, IEnumerable<OrderLine> lines)

{

var order = new Order(Guid.NewGuid(), customerId);

foreach (var line in lines)

{

order.AddLine(line.ProductId, line.Quantity, line.UnitPrice);

}

if (!order._lines.Any())

{

throw new InvalidOperationException("Order must have at least one line.");

}

order.Status = OrderStatus.Active;

return order;

}

public void AddLine(Guid productId, int quantity, decimal unitPrice)

{

if (quantity <= 0)

{

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException(nameof(quantity));

}

if (Status != OrderStatus.Draft && Status != OrderStatus.Active)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException("Can only change draft or active orders.");

}

_lines.Add(new OrderLine(productId, quantity, unitPrice));

}

public void MarkPaid()

{

if (Status != OrderStatus.Active)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException("Only active orders can be marked as paid.");

}

Status = OrderStatus.Paid;

}

}

public class OrderLine

{

public OrderLine(Guid productId, int quantity, decimal unitPrice)

{

ArgumentOutOfRangeException.ThrowIfNegativeOrZero(quantity);

ProductId = productId;

Quantity = quantity;

UnitPrice = unitPrice;

}

public Guid ProductId { get; }

public int Quantity { get; }

public decimal UnitPrice { get; private set; }

public decimal Total => Quantity * UnitPrice;

}

public class Customer(Guid id, string email, decimal creditLimit)

{

public Guid Id { get; } = id;

public string Email { get; private set; } = email;

public decimal CreditLimit { get; private set; } = creditLimit;

public decimal AvailableCredit { get; private set; } = creditLimit;

public void ReserveCredit(decimal amount)

{

if (amount <= 0)

{

throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException(nameof(amount));

}

if (AvailableCredit < amount)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException("Insufficient available credit.");

}

AvailableCredit -= amount;

}

}

Now introduce repositories to retrieve and persist these aggregates.

public interface IOrderRepository

{

Task<Order?> GetByIdAsync(Guid id, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

Task AddAsync(Order order, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

}

public interface ICustomerRepository

{

Task<Customer?> GetByIdAsync(Guid id, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

}

EF Core implementations (simplified):

public class AppDbContext : DbContext

{

public DbSet<Order> Orders => Set<Order>();

public DbSet<Customer> Customers => Set<Customer>();

public AppDbContext(DbContextOptions<AppDbContext> options)

: base(options)

{

}

protected override void OnModelCreating(ModelBuilder modelBuilder)

{

modelBuilder.Entity<Order>()

.HasKey(o => o.Id);

modelBuilder.Entity<Order>()

.Property(o => o.Status)

.HasConversion<string>();

modelBuilder.Entity<Order>()

.HasMany(typeof(OrderLine), "_lines");

modelBuilder.Entity<Customer>()

.HasKey(c => c.Id);

}

}

public class EfCoreOrderRepository(AppDbContext dbContext) : IOrderRepository

{

public async Task<Order?> GetByIdAsync(

Guid id,

CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

return await dbContext.Orders

.Include(o => o.Lines)

.SingleOrDefaultAsync(o => o.Id == id, cancellationToken);

}

public Task AddAsync(Order order, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

dbContext.Orders.Update(order);

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

}

public class EfCoreCustomerRepository(AppDbContext dbContext) : ICustomerRepository

{

public async Task<Customer?> GetByIdAsync(

Guid id,

CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

return await dbContext.Customers

.SingleOrDefaultAsync(c => c.Id == id, cancellationToken);

}

}

With this in place, you are ready to see how Unit of Work changes the shape of your code.

Before: Place Order Endpoint With Ad Hoc SaveCalls

Here is a Minimal API endpoint that coordinates placing an order, reserving credit, and writing a simple audit log. Everything uses AppDbContext directly.

app.MapPost("/orders/place", async (

PlaceOrderRequest dto,

AppDbContext db,

CancellationToken ct) =>

{

var customer = await db.Customers

.SingleOrDefaultAsync(c => c.Id == dto.CustomerId, ct);

if (customer is null)

{

return Results.NotFound("Customer not found.");

}

// Reserve credit and save immediately

var orderLines = dto.Lines

.Select(l => new OrderLine(l.ProductId, l.Quantity, l.UnitPrice))

.ToList();

var prospectiveOrder = Order.Create(dto.CustomerId, orderLines);

var amount = prospectiveOrder.TotalAmount;

try

{

customer.ReserveCredit(amount);

}

catch (InvalidOperationException ex)

{

return Results.BadRequest(ex.Message);

}

await db.SaveChangesAsync(ct); // First commit

// Create and save order separately

db.Orders.Add(prospectiveOrder);

await db.SaveChangesAsync(ct); // Second commit

// Write audit log separately

db.AuditLogs.Add(new AuditLog

{

Id = Guid.NewGuid(),

OccurredAtUtc = DateTime.UtcNow,

Message = $"Order {prospectiveOrder.Id} placed for customer {customer.Id}."

});

await db.SaveChangesAsync(ct); // Third commit

return Results.Created($"/orders/{prospectiveOrder.Id}", new

{

prospectiveOrder.Id,

prospectiveOrder.Status,

prospectiveOrder.TotalAmount

});

});

Problems:

- Three separate

SaveChangesAsynccalls for one logical operation - If something fails after credit is reserved but before the order is written, the system is inconsistent

- There is no single place you can point to and say “this is the commit for Place Order”

This is exactly the situation Unit of Work is meant to address.

After: Place Order Endpoint With Unit Of Work

Introduce an application service that knows how to place an order inside a Unit of Work boundary.

public sealed class PlaceOrderRequest

{

public Guid CustomerId { get; set; }

public List<OrderLineDto> Lines { get; set; } = new();

}

public sealed class OrderLineDto

{

public Guid ProductId { get; set; }

public int Quantity { get; set; }

public decimal UnitPrice { get; set; }

}

public interface IAuditLogWriter

{

Task LogAsync(string message, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

}

public class EfCoreAuditLogWriter(AppDbContext dbContext) : IAuditLogWriter

{

public Task LogAsync(string message, CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

dbContext.Add(new AuditLog

{

Id = Guid.NewGuid(),

Message = message,

OccurredAtUtc = DateTime.UtcNow

});

return Task.CompletedTask;

}

}

Application service:

public interface IOrderApplicationService

{

Task<Guid> PlaceOrderAsync(

PlaceOrderRequest request,

CancellationToken cancellationToken = default);

}

public class OrderApplicationService(

IOrderRepository orders,

ICustomerRepository customers,

IAuditLogWriter auditLog,

IUnitOfWork unitOfWork)

: IOrderApplicationService

{

public async Task<Guid> PlaceOrderAsync(

PlaceOrderRequest request,

CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

await unitOfWork.BeginAsync(cancellationToken);

try

{

var customer = await customers.GetByIdAsync(request.CustomerId, cancellationToken);

if (customer is null)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException("Customer not found.");

}

var lines = request.Lines

.Select(l => new OrderLine(l.ProductId, l.Quantity, l.UnitPrice))

.ToList();

var order = Order.Create(request.CustomerId, lines);

customer.ReserveCredit(order.TotalAmount);

await orders.AddAsync(order, cancellationToken);

await auditLog.LogAsync(

$"Order {order.Id} placed for customer {customer.Id}.",

cancellationToken);

await unitOfWork.CommitAsync(cancellationToken);

return order.Id;

}

catch

{

await unitOfWork.RollbackAsync(cancellationToken);

throw;

}

}

}

Minimal API endpoint becomes thin:

app.MapPost("/orders/place", async (

PlaceOrderRequest dto,

IOrderApplicationService service,

CancellationToken ct) =>

{

try

{

var orderId = await service.PlaceOrderAsync(dto, ct);

return Results.Created($"/orders/{orderId}", new

{

Id = orderId

});

}

catch (InvalidOperationException ex)

{

return Results.BadRequest(ex.Message);

}

});

Now the business operation:

- Begins a unit of work

- Loads customer and validates credit

- Creates the order aggregate

- Reserves credit

- Writes an audit log

- Commits exactly once

If anything fails before CommitAsync, SaveChangesAsync never runs. If you later add explicit transactions, RollbackAsync will actually revert the database state.

The important part is not the specific implementation. The fact that you have made the operation’s commit point visible.

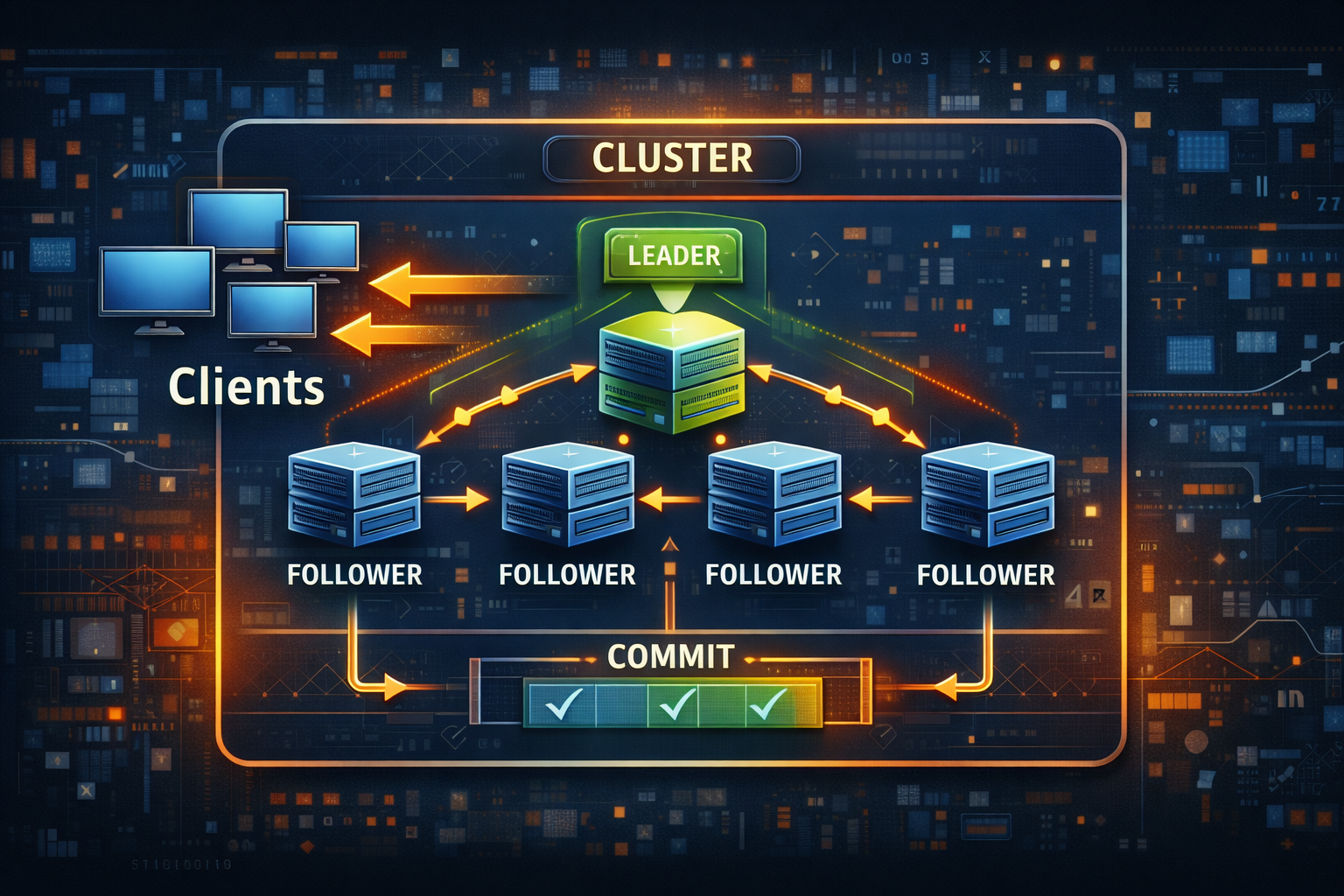

Using Explicit Database Transactions

If you want stronger control, you can extend EfCoreUnitOfWork to manage explicit transactions.

using Microsoft.EntityFrameworkCore.Storage;

public class EfCoreUnitOfWorkWithTransaction(AppDbContext dbContext) : IUnitOfWork

{

private IDbContextTransaction? _currentTransaction;

public async Task BeginAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

if (_currentTransaction is not null)

{

return;

}

_currentTransaction = await dbContext.Database.BeginTransactionAsync(cancellationToken);

}

public async Task CommitAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

await dbContext.SaveChangesAsync(cancellationToken);

if (_currentTransaction is not null)

{

await _currentTransaction.CommitAsync(cancellationToken);

await _currentTransaction.DisposeAsync();

_currentTransaction = null;

}

}

public async Task RollbackAsync(CancellationToken cancellationToken = default)

{

if (_currentTransaction is not null)

{

await _currentTransaction.RollbackAsync(cancellationToken);

await _currentTransaction.DisposeAsync();

_currentTransaction = null;

}

}

}

Your application service remains unchanged. You just swap implementations in DI.

builder.Services.AddScoped<IUnitOfWork, EfCoreUnitOfWorkWithTransaction>();

This is where the abstraction starts to pay off.

When To Use The Unit Of Work Pattern

Unit of Work earns its place in your architecture when you care about business-level consistency.

Situations where it makes sense:

Multi-repository operations

A single use case touches:

- Orders

- Customers

- Inventory

- Audit logs

You want:

- All changes to succeed together

- Or all of them to revert

Unit of Work gives you that boundary.

Non-trivial domain rules

Money, reservations, and coordination of scarce resources rarely tolerate partial commits. If your domain has these kinds of rules, you want explicit control over when a transaction begins and commits.

Rich domain model with repositories and service layer

If you have already invested in:

- Domain Model

- Repository pattern

- Application services

Unit of Work is the glue that turns “a bunch of repository calls” into a single business operation with a clear commit point.

Anticipated transactional complexity

If you expect to add:

- Outbox pattern

- External message publishing that must align with the database state

- Cross-service or cross-database coordination

a Unit of Work abstraction is the future seam for that work.

When Not To Use The Unit Of Work Pattern

Unit of Work is not mandatory. Some scenarios do not justify the extra abstraction.

Situations where it may be overkill:

Simple CRUD with one repository

If an endpoint:

- Loads a single entity

- Applies a small change

- Calls

SaveChangesAsynconce

then wrapping that in a full Unit of Work abstraction might add boilerplate. A scoped DbContext with a single commit at the end of the handler is often enough.

Read-only operations

Pure queries do not need a Unit of Work. Focus instead on projection models and performance.

Truly independent actions

Sometimes a single HTTP request triggers two operations that are intentionally independent, for example:

- Logging analytics events

- Updating user preferences

If those do not need to roll back together, forcing them into one transaction may reduce throughput and complicate error handling. In that case, separate Units of Work or independent commits make sense.

Anti-pattern: repositories that still call SaveChanges

One common misuse:

- You introduce

IUnitOfWork - You keep calling

SaveChangesAsyncinside repository methods

At that point, you have two commit concepts competing with each other. Decide which layer owns persistence commits. If you adopt Unit of Work, repositories should only modify tracked entities, not flush changes.

Bringing Unit Of Work Into An Existing App

You can retrofit the Unit of Work gradually.

A simple path:

- Search for every call to

SaveChangesAsync. - Move those calls out of repositories and domain services into application services or endpoints.

- Wrap the commit point for one nontrivial use case in

IUnitOfWork.CommitAsync. - Introduce

BeginAsyncandRollbackAsynconly if needed. - Observe how much easier it becomes to reason about what each operation actually does to the database.

If the experiment makes the code clearer, continue with other use cases. If it does not, you learned something about your current complexity level.

Closing Thought

Unit of Work is not about ceremony. It is about honesty.

Every non-trivial business operation already acts like a unit. Either the entire thing makes sense as a whole, or you end up explaining “partial success” to users and auditors.

When you let SaveChangesAsync hide in random services, you deny that reality. When you give it a name and an interface, you acknowledge it and take control.

Treat your important use cases as first-class units. Then make the database follow that decision, not the other way around.